[Image description: A photo of the DSV Limiting Factor and its launch ship, the DSSV Pressure. The photo is taken about eye-level with the ocean as the Limiting Factor, a white, rectangular module is lowered by a mechanical arm into the sea. A person can be seen on the DSSV directing this process. End description.]

We finally have a submersible vehicle that can reach any point in the ocean, designed to last. It has already reached the bottom of the Challenger Deep four times, and the deepest points of all five oceans. This is where the project derives its name: The Five Deeps. Its progenitor, Victor Vescovo, funded it as part of his “Five Deeps Challenge.” But I wonder, should something this really be a challenge?

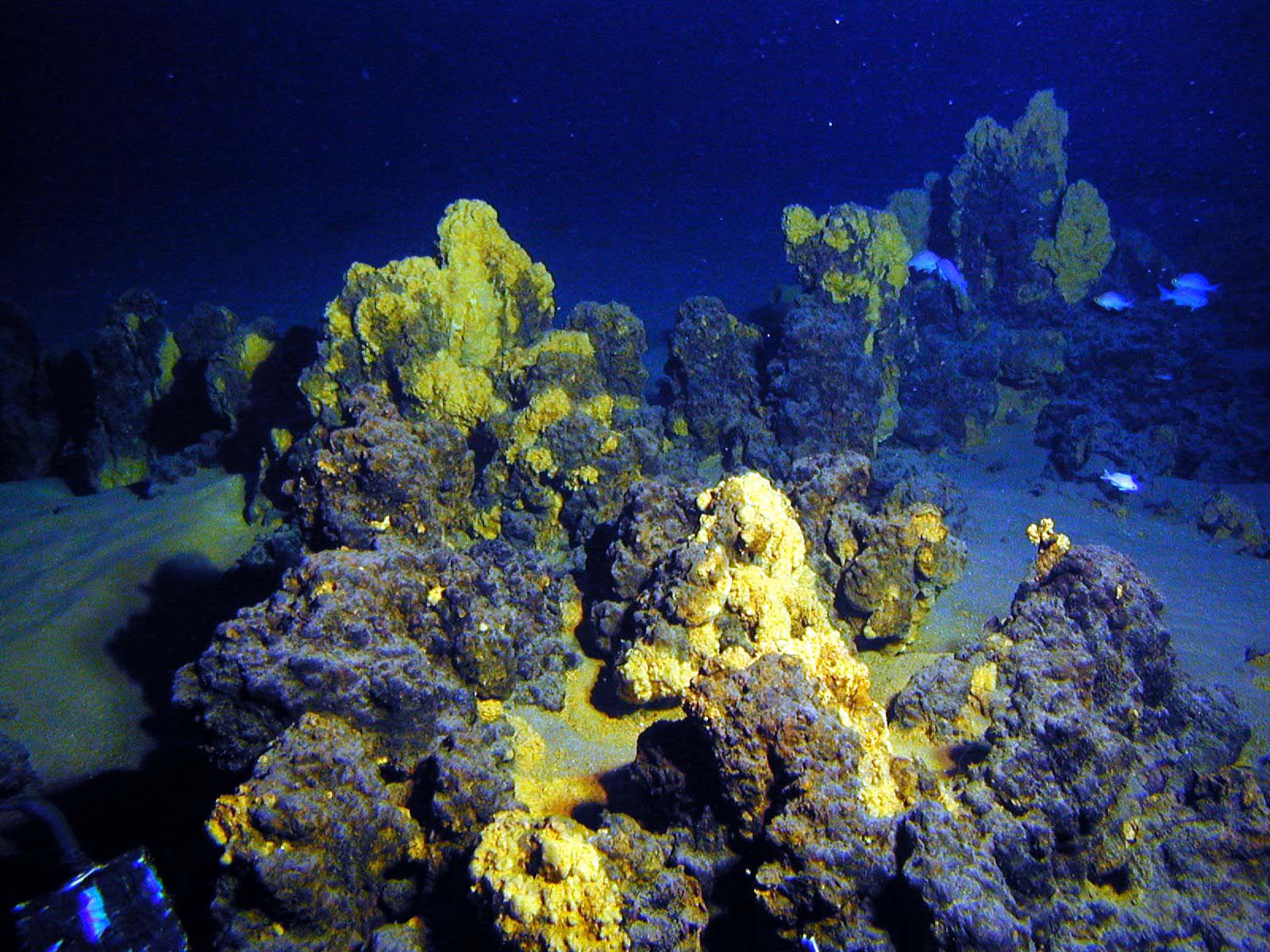

This article is the most comprehensive I can find. The implications of this entire project are fascinating, and the DSV Limiting Factor has already greatly contributed to deep-ocean science. In a relatively short time, our maps of the ocean floor, especially the trenches (which the team has been working closely with) have been greatly improved and corrected. There have been several discoveries of new animal species, including one described as “an extraordinary gelatinous animal” with more certain to be on the way. Unlike the other two submersibles that have reached the bottom of the Challenger Deep, which only ever completed the feat once, this one was built to stick around.

Victor Vescovo funded the project and owns the DSV Limiting Factor. A daredevil and thrill-seeker, he has reached all Seven Summits of the World, and both North and South poles. This is known as the “Grand Slam” of adventuring. Add the trenches, and he has now completed the nascent “Five Deeps” and “Four Corners” challenges. But is this something we should really be promoting? The article also proposes the idea of a company that provides tourism to the Challenger Deep for a high price tag. This has me worried. Extreme tourism has many issues. For example, in recent years, tourism to Mount Everest has come under fire. People die all the time on Mt. Everest because companies allow unqualified people – people with no mountaineering experience whatsoever – to summit the mountain with a team of guides. This puts both the lives of the tourists and the guides at risk, as well as the lives of rescue and body recovery teams necessary on such a highly trafficked mountain. Even experienced climbers can and often do die on the mountain. Vescovo is a retired naval officer. He has a degree of oceanic experience that many others do not share. Even so, he insisted on doing the first of the dives alone, against the advice of other people on the project and the collaborative spirit of science. How much experience would the guides that run these tours have? The tourists themselves? On Everest, people succumb to a mindset called “summit fever” that causes them to seek the summit even under changing weather and unfavorable conditions. Summit fever can be deadly. To launch the submersible, clear oceanic conditions are necessary. They are hard to come by. The dive is a six or seven hour round trip in a very small vehicle. Would these prospective Challenger Deep tourists be willing to listen if the dive had to be scrapped before or during the mission? What if someone gets claustrophobic halfway down?

I also wonder about the viability of such a piece of equipment being in the hands of a single person. Now that it’s been proven possible, I’m certain there will be work to build other reusable deep-ocean submersibles. Nonetheless, what happens when the DSV Limiting Factor is sold, as Vescovo plans to do? Will it be treated like a valuable piece of research equipment or a toy in the hands of its next buyer? What percentage of science should be about thrill-seeking and what percentage about discovery? To what extent can these attitudes coexist? I have no easy answers, just uneasy thoughts and tentative hopes for the new frontier of oceanic exploration posed by the development of the Limiting Factor.